In a 7-0 decision the Nevada Supreme Court ruled this week to deny the final appeal of death-row inmate Robert Ybbara, 56, to strike the death penalty.

In a 7-0 decision the Nevada Supreme Court ruled this week to deny the final appeal of death-row inmate Robert Ybbara, 56, to strike the death penalty.

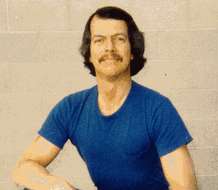

Ybarra, convicted of raping, beating and burning to death Nancy Griffith, 16, in 1979, has been in death row for more than three decades.

In 1981 a jury sentenced Ybarra to death, but two decades later, the United States Supreme Court held the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment precludes the execution of mentally retarded persons, and the Nevada Legislature adopted a statutory provision to address claims of mental retardation involving defendants like Ybarra who were sentenced to death before the Supreme Court decision.

In the 31 years that have passed since his conviction Ybarra has attempted several unsuccessful appeals, the most recent, and final, on Sept. 2, 2010.

Michael Pescetta, assistant federal public defender, Las Vegas, in a Sept. 2, 2010, Las Vegas Review-Journal article, told the court his client was mentally disabled and ineligible to receive the ultimate punishment.

The then White Pine County District Attorney Richard Sears quoted in the same article said there was no evidence Ybarra was ever tested for mental retardation and that any tests conducted now wouldn’t prove Ybarra’s status then.

“He’s been on psychotropic medicine for 30 years,” Sears said. “How will we know what his IQ was with that kind of drugging?”

Back in December 2005, the Nevada Supreme Court issued an order for the Seventh Judicial District Court in Ely to hold a hearing and rule on Ybarra’s mental competency.

Ybarra’s attorney sought relief under that Supreme Court ruling, asking the district court to set aside the death sentence on the ground that his client was mentally retarded.

In the high court’s March 3 ruling, Chief Justice Ron Parraguirre, writes:

“Because Ybarra failed to meet his burden of demonstrating bias based on Judge Dobrescu’s prior professional relationship with the murder victim’s family or the notoriety of his case, his (Ybarra’s) disqualification motion was unsupportable and properly denied.

“As to Ybarra’s mental retardation claim, we conclude that he failed to prove by a preponderance of the evidence that he suffered from significant subaverage intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior deficits during the developmental period, which extends to 18 years of age. Consequently, he failed to show that he is mentally retarded as provided in NRS 174.098(7). We therefore affirm the district court’s order denying Ybarra’s motion to strike the death penalty.”

On the issue of questioning Dobrescu’s objectivity, Pescetta said in the Las Vegas Review-Journal article, “Ruling in Ybarra’s favor” would have undoubtedly cost Dobrescu an election, adding the judge had a conflict of interest because he once prepared a standard will for the victim’s parents.

The court rejected this argument in 2007, ruling the minor legal work did not rise to the level of conflict requiring a judge to remove himself from the case.

However Ybarra is not alone of the 85 inmates on Nevada death row more than half have been there for over a decade and at least a dozen have been there 20 years or more.

However Ybarra is not alone of the 85 inmates on Nevada death row more than half have been there for over a decade and at least a dozen have been there 20 years or more.

And since the death penalty was reinstated only one death row inmate was executed after exhausting all appeals. The other four men simply opted out of the appeals process in a kind of suicide by the state.

While most critics place the blame of the lengthy appeals process on the Ninth Federal Circuit Court blame must also be shared by the Nevada Supreme Court.

Ybarra for example has appealed and has his sentence delayed no less than five times by the Nevada Supreme Court including his most latest attempt.

In fact it is the interplay between appealing to the state then appealing to the federal level that has been perfected by Ybarra and other long serving death row inmates.

“The way the system is set up you can send an appeal to the state and then appeal the decision to the feds.” said one defense attorney who declined to be identified. “It can be virtually endless.”

Apart from staving off death by lethal injection which is reward in itself many death row inmates also out hope that the death penalty itself will be abolished as it was in 1974.

While support for it especially in Nevada and other western states has never fallen below 60 percent there are signs that on the federal level could well indeed abolish the death penalty. Just this year the US high court ruled that executing minors and mental defectives was cruel and unusual punishment.

Ybarra was not the only resident of death row to seek an out because of ruling literally hundreds of appeals either directly or indirectly related to the federal ruling.

“Every time there is a federal ruling it opens another door for other death row inmates.” the attorney continued. “They are probably not going to win but winning isn’t the only objective the real point is to gain more time.”

More time for the high court for the court to abolish the death penalty altogether and/or more for the public to grow disgusted with the system and scrap the death penalty as unworkable.

While the death penalty is still supported by an overwhelming percentage of the population support is waning even in Nevada when the sentence takes decades to carry out.

“It is especially frustrating for a guy like Ybarra,” said former White Pine county Sheriff Bernie Romero in 2006. “Here is a guy who confessed to the killing, was found guilty with overwhelming amount of evidence. Sentenced by a jury of his peers and now spend 25 years appealing.”

Romero was a newly minted detective when he arrested Ybarra in 1979, he retired from law enforcement after losing his bid for a third term in 2006.

Ybarra does not even have a claim of redemption the much more famous Stanley “Tookie” William’s has made in an effort to win clemency in California.

He is described as a wimp and a braggart by both correctional officers and other inmates on death row who sometimes tries to commit suicide but never quite succeeds or has a last minute change of heart.

In his over quarter of a century incarcerated he has done very little except study his case. And if one had to serve time one could do worse than Ely’s Death row. Although conditions are spartan they are considered the most comfortable in the whole prison.

“You have to understand this is our home,” Ybarra said in an interview with the High Desert Advocate in 1992. “We aren’t going to be gone for five or ten years

The death row pod had at the time its own weight set, television and eating area and it did have a homey feel. It was also cleaner than much of the rest of the prison and because it is death row much more secure than the general population.

Among the things Ybarra has not done was to study to become a priest as he promised to do to if the jury gave him life without parole instead of the death penalty.

“I am very sorry for what I’ve done,” he pleaded back in 1981 “I truly regret sacrificing Nancy for Satan. I want to make up for all the pain and suffering I’ve caused my parents. I wish to God I could do something to make it up to Nancy’s mother, sister, and brothers. If you give me life in prison, I could further my education and get involved with the church like I used to. I could study and become a priest like I’ve wanted to since I was little. Please give me life in prison, I beg of you, don’t give me the death penalty.”

If Ybarra had been spared the death penalty he would have been just another aging forgotten inmate in the general population without the strange kind of celebrity he garners every two or three years.